“I’ve seen better landings where everyone’s been killed.” That was an aside from one of my earliest instructors, and it happened on a day that wasn’t my finest as a student pilot. If there was something that could be done wrong, I was doing it. Airspeed. Power. Altitude. Heading. Slipping and skidding. All felt like they were in a blender, and it wasn’t making a nutritious power drink either.

The “…everyone’s been killed…” part came when I was demonstrating – and not aware of it at the time – that a low, dragged-in approach well below the glideslope just wasn’t setting me up for a greaser of a landing. Much the opposite as I kept adding power (at least I was aware of the fact that our airspeed was way too low), almost to no avail, while the runway was disappearing below the nose, which kept getting higher and higher on the horizon.

I clearly remember curling my toes as we mushed over the runway threshold, to a resounding “thump!” as my poor aircraft absorbed what to my mind at the time was just a little less than a full-blown crash. And it was all the result of my being held prisoner in the infamous “behind the power curve “ lockup. I plead guilty!

As with all ‘learning experiences’ there was a silver lining. My instructor let me go as far as was safe so that I learned a BIG lesson about what not to do. His philosophy was that early in the game, students need to see the error of their ways, and you don’t get there by mollycoddling them, or by flying perfect circuits through judicious instructor input along the way. This particular incident happened more than 40 years ago and still stays with me as clear as can be.

So, let’s review the dynamics behind flight in the often misunderstood region of reversed command.

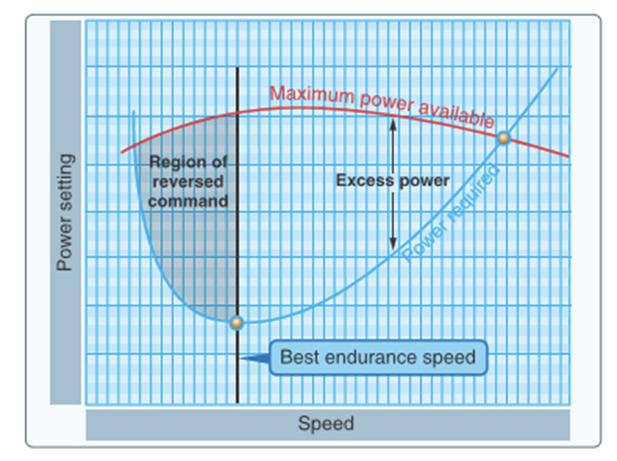

Why is it so named? Take a look at the Power versus Speed diagram. To the left of the best endurance speed is the region of reversed command, also referred to as the back-side of the power curve. To the right is the region of normal command/front side of the power curve. On the back-side, the slower you go, the more power is required to maintain a specific airspeed. This is the reverse of flight on the front side of the power curve, where the slower you go, the less power required to maintain a specific airspeed.

I’ve heard novices (and some experienced pilots as well) say: “Then why fly in that area of flight at all?”. Well, for one, if you’re going to take off or land, you will naturally be transiting through the region of reversed command.

That’s just for starters. In aerial application, you are very often required to fly at airspeeds below best endurance speed – particularly in turns – on account of large initial loads and limited excess thrust during the first few swaths of a field application. This is particularly true with round engines which, while having considerable horsepower, add a significant amount of drag because of their large frontal area. Which means you have less excess thrust to play with.

Sound familiar? We’ve all been there, as in when you pull up off the first spray run turning downwind in a procedure turn for the next swath, and it feels like you’re balancing on a beach ball, controls just a bit sloppy and an aircraft that just feels ‘doggy’. That’s telling you “Easy does it!” here in the region of reversed command, so you don’t enter stall/spin territory, a place you really don’t want to be!

I also found a somewhat novel way to slide into the backside of the power curve. A few years ago I was asked to ferry a turbine Thrush to an ag airstrip some miles away from home base. The destination airstrip was plenty long, but only about 30 feet wide, so I fell into the clever trap of being late in my roundout awaiting the same flare sight picture of the much wider (150 feet) runway at home base. (Remember those illusions of flight?). But just to add to the fun, I didn’t notice that the airspeed indicator was in knots, not miles per hour as the majority of Thrush’s I had flown. So I happily set up on final with what I thought was 80 mph. As opposed to what was in actuality 92 mph!

These two factors, plus the fact I had ‘let my guard down’ after a long day flying at home base, resulted in a ‘boing, boing!” porpoising action that had me promptly back in the air, hanging on the prop and wishing I was elsewhere rather than well into the region of reversed command. Thank goodness for a 750 hp turbine and an empty hopper that saved my bacon (with some prompt corrective action on my part of course).

As the aviation gods have a funny sense of humor, there are a lot of other easy routes into the region of reversed command, first and foremost having little or no experience on a particular aircraft. Another classic example is reefing an aircraft into the air before it is ready to fly. Or how about climbing out of ground effect with an increasing tailwind due to wind shear? Lots of fun for everyone!

In regards to flight behind the power curve, here is a valuable exercise that you can (and should) do with any new aircraft, or indeed at the beginning of each spray season even if you are well experienced on the aircraft. This is particularly true in ag aviation where your checkout can often be something along the lines of “It’s parked behind the hangar. Keys are in it”.

First and foremost, as part of any new aircraft transition, practice slow flight at altitude. You’ll get a first-hand look at how the airplane performs, and how the controls feel as you get well into the region of reversed command. Start in trimmed level flight at cruise power setting. Reduce airspeed In 10 mph increments – stabilizing at each airspeed – and note power setting, and how the aircraft handles at each particular point.

Once below best endurance speed you’ll be in a flight regime you’ll often see when doing fieldwork – again, particularly in the turns – and there’s nothing like “training the hands” to recognize potential areas of the flight envelope that could make for unneeded excitement if you are just a bit inattentive. Ag flying is enormously satisfying just from a piloting point of view alone, particularly because you get very good at ‘stick and rudder’ flying, such as being fully aware of your aircraft’s flight characteristics in the region of reversed command.

NOTE: Power curve diagram from the FAA Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (2016), Figure 11-14, p. 11-12.